Fragile Anchors: Trust, Nationalism, and the Great Power Juggle

From gold’s resurgence amid U.S. fragility to Europe’s nationalist surge, Gulf unease over a China–Russia energy axis, and Pakistan’s diplomacy.

Americas — Gold’s Resurgence Amid Waning Trust in U.S. Institutions

Gold, the ancient store of value, is enjoying a new moment of geopolitical prominence. Central banks—from Ankara to Beijing—are buying the metal at record levels, motivated less by inflation and more by doubts about America’s ability to sustain its global role. Washington’s ballooning debt, political polarization, and increasingly visible challenges to the Federal Reserve’s independence have raised questions about the durability of the dollar-based order.

For decades, the dollar was not just a currency but a strategic anchor. Its dominance in trade and reserves allowed the United States to project financial power as effectively as military might. But recent trends suggest a fraying consensus. The 2008 financial crisis was the first great shock. The sanctions tsunami unleashed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine accelerated the search for alternatives, as countries realized how vulnerable they were to dollar-based enforcement. Gold, unlike fiat money, is immune to politics.

The surge recalls the Cold War era, when states hoarded bullion as insurance against superpower confrontation. Today, the anxiety is not about nuclear brinkmanship but about fiscal and institutional fragility inside the U.S. itself. If Washington appears unable to manage its own finances or safeguard the neutrality of its central bank, allies and rivals alike will hedge.

Our Take: America’s greatest strength—the credibility of its institutions—is slowly being tested. Gold’s resurgence is less about the metal itself than the doubts it signals. The thin red line here is between temporary turbulence and a deeper erosion of faith in the dollar system.

Europe — The Surge of the Right: Anti-Immigration Politics Across Europe

Across Europe, populist and right-wing movements are riding a new wave of support. From Berlin to Lisbon, immigration has emerged as the defining fault line. In Britain, anti-immigration protests have grown more frequent and more heated. Germany, once a bastion of post-war liberalism, has gone so far as to classify the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) as an extremist movement. Portugal’s Chega party, once a fringe presence, now commands a solid bloc in parliament. And in Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni treads a careful path—balancing nationalist rhetoric with pragmatic labor migration policies.

Image: A banner advocating "remigration" during an anti-immigration protest in Calais, France © Jérémy-Günther-Heinz Jähnick, CC-by-GFDL 1.2

This is not Europe’s first populist moment. The continent has cycled through waves of anti-immigrant sentiment before, from the backlash against Turkish workers in 1970s Germany to the refugee crisis of 2015. But today’s surge feels different because it coincides with a broader questioning of Europe’s liberal order. Stagnant economies, overstretched welfare systems, and fears of cultural erosion are fueling a sense that mainstream politics no longer defends “the people.”

For Brussels, this trend is troubling. The European Union was built on the premise that national chauvinism could be tamed through integration. But as nationalist movements inch closer to power, they push the boundaries of that consensus. Liberal red lines—on asylum, human rights, and the rule of law—are under pressure.

Our Take: Europe’s history shows that when nationalism moves from the fringes to the mainstream, the center can unravel quickly. The thin red line lies in whether liberal democracies can absorb and channel discontent without compromising their foundational principles.

Middle East — China–Russia Energy Diplomacy and Its Gulf Reverberations

When Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin clasp hands in Moscow, the gesture is more than symbolic. It marks the deepening of an energy partnership explicitly designed to challenge U.S. influence. Russia, isolated by sanctions, is redirecting its hydrocarbons eastward. China, hungry for secure supplies, is happy to oblige. The result: a budding Eurasian energy axis.

For Gulf monarchies, this shift raises difficult questions. For decades, their oil and gas exports have flowed westward, with Washington as both market guarantor and security patron. Now, pipelines from Siberia to Xinjiang and deals denominated in yuan threaten to erode the Middle East’s privileged position in the energy hierarchy. Gulf producers still command vast reserves and low extraction costs, but their leverage diminishes if Eurasia can meet more of China’s needs directly.

This realignment does not mean the Gulf will be abandoned. On the contrary, China remains the region’s largest energy customer, and Russia cannot replace Gulf volumes. But the symbolism matters. If Moscow and Beijing can cooperate to weaken the dollar’s hold over energy trade, they create a precedent for others to follow. That undercuts the implicit bargain on which Gulf power has rested for decades: oil priced in dollars, secured by American might.

Our Take: Gulf leaders are watching carefully. The thin red line is whether China and Russia’s partnership becomes a complementary relationship to Gulf exports—or an eventual substitute that reduces their strategic clout.

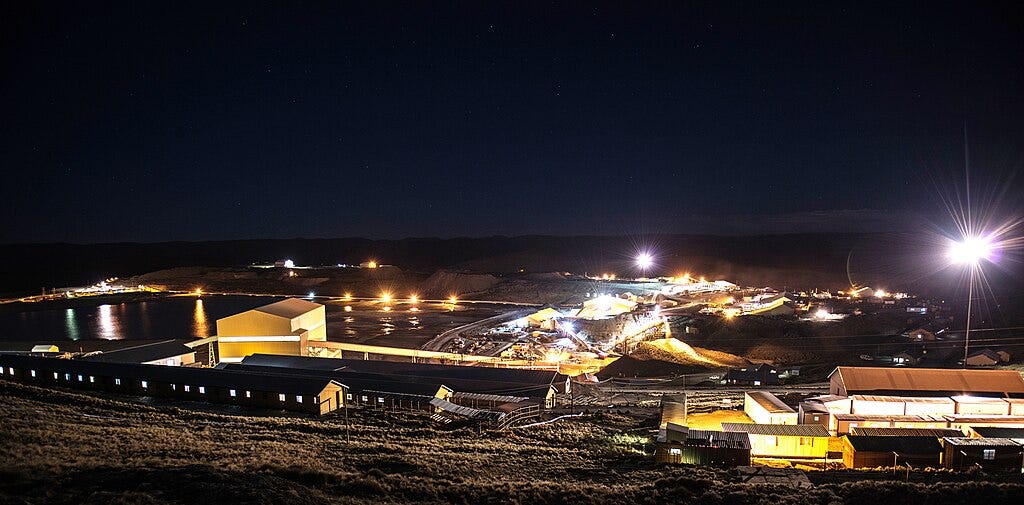

Africa — Lesotho’s Diamond Mine Cuts Workforce Amid Global Slump

High in the Maluti mountains, Lesotho’s Letseng mine has long been a source of pride. Famous for producing some of the world’s largest diamonds, it has provided jobs, foreign exchange, and a rare global foothold for a tiny landlocked country. But this week, management announced the layoff of roughly 20 percent of its workforce, citing collapsing global demand.

Image: Letšeng Diamond Mine in Lesotho, CC BY-SA 3.0

The news is grim for Lesotho but emblematic of a broader African dilemma. Many economies on the continent remain tethered to commodity cycles. When prices rise, governments enjoy windfalls; when they fall, the social and political costs are immediate. The 2008 financial crisis revealed this fragility. A decade later, the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced it. Now, a diamond slump underscores how dependent African states remain on global whims.

Economists have long urged diversification: agriculture, manufacturing, services. Yet structural barriers—weak infrastructure, limited capital, and entrenched patronage networks—make such transitions painfully slow. For resource-dependent states, downturns not only threaten growth but also risk political instability, as unemployed miners and disillusioned youth vent frustrations against fragile governments.

Our Take: Lesotho’s mine cuts are more than a local story. They are a reminder that Africa’s economic resilience still hinges on breaking free from commodity dependency. The thin red line here is between cyclical hardship and systemic fragility that can spill into political crisis.

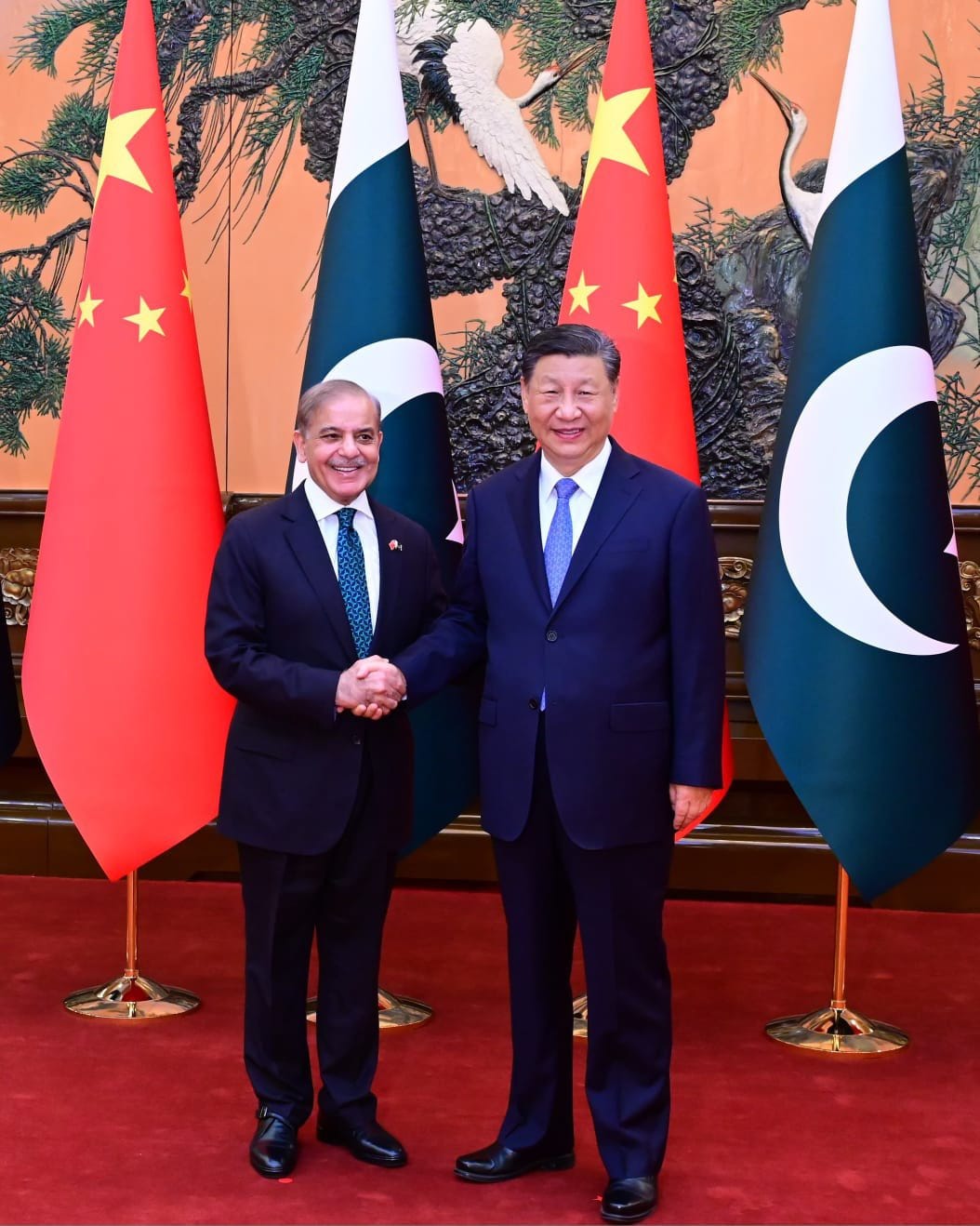

Asia Pacific — Pakistan’s Tightrope Between Washington and Beijing

When Pakistan’s Army Chief, General Asim Munir, traveled to Washington this summer, it was more than a diplomatic courtesy. It was a signal. Islamabad is seeking to reengage Washington even as it remains bound, strategically and materially, to Beijing. For Pakistan, the challenge is not merely about hedging—it is about survival in a shifting Asian chessboard.

Image: Pakistan’s PM Shehbaz Sharif with President Xi Jinping of China

China has long been Pakistan’s “iron brother.” Beijing supplies nearly 80 percent of its defense imports and anchors its infrastructure through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Plans for a “CPEC 2.0,” including extensions into Afghanistan, underscore how deeply Pakistan’s economic future is tied to Chinese capital. Yet cracks are visible. Beijing has scaled back financing for the vital Main Line-1 railway, leaving Islamabad scrambling for loans from multilateral banks. More troubling still for Pakistan, China is visibly warming to India—deepening trade links and holding high-level summits. For Islamabad, that is an earthquake in slow motion.

Munir’s Washington outreach is meant to widen Pakistan’s options. U.S. officials remain skeptical but see Pakistan as useful for its geography—bordering Afghanistan, near Iran, and sitting astride sea routes into the Indian Ocean. Yet Washington’s support is limited and transactional. Meanwhile, Pakistan still relies overwhelmingly on Chinese arms and investment. Should Beijing tilt further toward New Delhi, Islamabad risks strategic downgrading.

India is watching closely. New Delhi has protested Munir’s Washington welcome, wary of any revived U.S.–Pakistan axis. At the same time, India has cultivated closer economic ties with Beijing, both to temper uncertainty in Washington and to secure its own leverage. China, for its part, may prefer to hedge—holding Pakistan close militarily while expanding economic opportunities with India.

That leaves Pakistan straddling a fragile line. A tilt too far toward Washington risks alienating Beijing. A lopsided dependence on China could render it irrelevant if Beijing prizes relations with India more.

Our Take: The thin red line here is stark: can Pakistan remain indispensable to both giants without becoming expendable to either? In an era of shifting great-power triangles, Pakistan once again finds itself playing the role it knows best—the swing state of South Asia. But this time, the stakes are higher.