The New Chokepoint Wars: Oil, Data, and the Geography of Disruption

The Houthis and Iran are testing the world’s tolerance for disruption—from oil in Hormuz to undersea cables in the Red Sea. The stakes are nothing less than the stability of globalization itself.

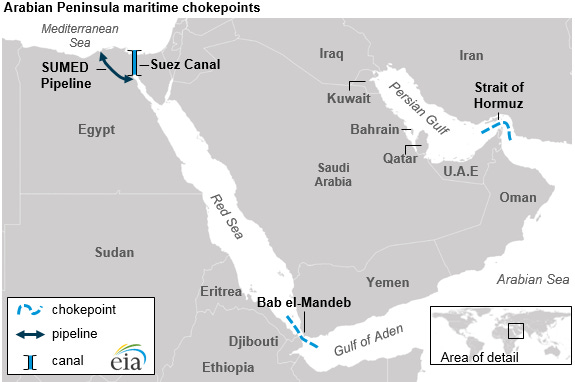

Iran and its Houthi proxies are systematically exploiting the world's most vulnerable maritime passages—the Strait of Hormuz and Red Sea—to extract geopolitical leverage while avoiding direct confrontation with Western powers. This campaign extends beyond traditional shipping disruption to include undersea cable sabotage, creating a new form of multi-domain coercion that keeps globalization's lifelines perpetually fragile. Rather than seeking outright closure of these critical passages, Iran has perfected a strategy of managed instability that imposes continuous costs on global commerce while maintaining escalation control. The approach reveals how non-state proxies can wield asymmetric power over the physical infrastructure of international trade, forcing major powers into reactive postures while the global economy absorbs mounting risk premiums across energy, shipping, and digital connectivity.

Image: “Map of Arabian Peninsula maritime chokepoints” by U.S. Energy Information Administration, CC BY 2.0

The Strategic Context

The geography of global commerce flows through a handful of maritime chokepoints that cannot be bypassed without enormous cost. The Strait of Hormuz carries approximately 21% of global petroleum liquids traffic, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The Red Sea-Suez Canal route handles 12% of global trade and 30% of global container traffic. These passages represent what strategists call "strategic geography"—terrain so vital that controlling or threatening it confers disproportionate leverage.

Iran has spent decades studying these vulnerabilities. Since the 1980s Tanker War, Tehran has refined tactics for chokepoint coercion: mining, fast-boat swarms, anti-ship missiles, and proxy harassment. What has evolved since 2023 is the sophistication of multi-domain operations that simultaneously threaten surface shipping and undersea infrastructure while maintaining plausible deniability.

The current campaign began with opportunistic Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping following the October 7 Hamas attacks on Israel. By early 2024, these had escalated into systematic targeting of commercial vessels, including the sinking of the MV Rubymar in February 2024 and attacks that damaged multiple tankers and container ships. Concurrently, three undersea internet cables in the Red Sea were severed between February and March 2024, disrupting connectivity across South Asia and the Arabian Peninsula.

Maritime Security Theater

Red Sea Operations

The Houthis have demonstrated remarkable tactical evolution in their maritime campaign. Initial attacks relied on relatively crude missile and drone salvos. By mid-2024, operations included naval mines, underwater drones, and what appears to be deliberate cable-cutting operations conducted by divers or submersibles.

Commercial shipping responses have been dramatic. Major carriers including Maersk, CMA CGM, and Hapag-Lloyd suspended Red Sea transits for extended periods. Those continuing passage face insurance premiums that have increased from roughly 0.1% of cargo value to over 1% for Red Sea transits. Lloyd's of London estimates additional war risk premiums have added $200-300 million monthly to global shipping costs since late 2023.

The economic geography is reshaping accordingly. Container traffic through Suez fell approximately 37% in the first half of 2024 compared to 2023, according to the Suez Canal Authority. Ships rerouting around Africa's Cape of Good Hope add 10-14 days and roughly $1 million in additional fuel costs for large container vessels.

Hormuz Pressure Points

Iran's approach in the Strait of Hormuz reflects greater strategic sophistication. Rather than attempting closure—which would trigger massive retaliation—Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy units conduct calibrated provocations that maintain tension without crossing clear red lines.

Since 2023, Iran has seized or attempted to seize at least eight commercial vessels in Gulf waters, typically releasing them after brief detention. These actions serve multiple purposes: gathering intelligence on commercial traffic patterns, testing international responses, and maintaining psychological pressure on energy markets. Oil futures typically spike 2-4% following such incidents before settling back as vessels are released.

More concerning are Iran's demonstrated mine-laying capabilities. In 2024, Revolutionary Guard units conducted highly publicized mine-laying exercises in the Strait while publicizing their inventory of naval mines. These exercises serve as deterrent signaling—Iran doesn't need to actually lay mines to extract their psychological value from energy markets.

Undersea Cable Vulnerabilities

The February-March 2024 cable cuts in the Red Sea exposed a new dimension of infrastructure vulnerability. The severed cables—including the SEA-ME-WE 5 and AAE-1 systems—carry substantial portions of internet traffic between Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia.

While cable breaks occur regularly due to ship anchors and seabed shifts, the clustering and timing of the Red Sea cuts coincided with escalated Houthi maritime operations. Repair operations were delayed by security concerns, extending service disruptions for weeks rather than days.

The global internet backbone relies on approximately 400 undersea cables carrying 95% of international data traffic. Unlike shipping, which can be rerouted at considerable cost, cable networks have limited redundancy. A small number of deliberate cuts can cascade into significant connectivity degradation across entire regions.

Economic Security Implications

Energy Market Dynamics

Despite widespread maritime disruptions, global energy prices have remained relatively stable due to several offsetting factors. OPEC+ production discipline has kept supply tight enough to absorb moderate demand destruction from higher shipping costs. Simultaneously, economic weakness in China and Europe has dampened overall energy demand growth.

However, this equilibrium masks underlying fragility. The International Energy Agency estimates that complete Hormuz closure would remove approximately 15-17 million barrels per day of crude and condensate from global markets—roughly 15% of total supply. Even temporary closure would likely drive oil prices above $150 per barrel, triggering recession risks globally.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve releases could provide temporary buffering, but U.S. reserves have fallen to approximately 350 million barrels—the lowest level since the 1980s. Gulf states maintain larger reserves but would face domestic political pressure during supply crises.

Commercial Shipping Adaptations

The shipping industry has demonstrated remarkable adaptability, but at considerable cost. Insurance markets have effectively repriced Red Sea risk, creating a two-tiered global shipping system where Middle Eastern routes carry permanent risk premiums.

Container shipping schedules have been restructured around Cape of Good Hope routing for many services, adding fleet capacity requirements and extending supply chain timelines. These adaptations impose permanent efficiency losses on global trade even when attacks subside.

More strategically concerning is the concentration of alternative routes. Cape routing creates new chokepoints at the Cape of Good Hope itself and increases traffic through the Strait of Malacca—already the world's busiest shipping lane and itself vulnerable to disruption.

Regional Realignment and Alliances

Gulf State Positioning

Gulf monarchies find themselves in an increasingly precarious position. Their prosperity depends on energy export security, yet their primary security guarantor—the United States—has limited appetite for sustained military escalation with Iran.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE have pursued hedging strategies, maintaining diplomatic engagement with Tehran while quietly expanding naval cooperation with international partners. The UAE has invested heavily in Red Sea port facilities in Egypt and logistics infrastructure that could provide alternative routing during crises.

Bahrain and Kuwait, given their proximity to Iranian naval bases, have focused on hardening critical infrastructure and expanding strategic reserves. These adaptations reflect a broader regional recognition that chokepoint wars may become a permanent feature of Gulf security rather than temporary crises.

Allied Response Coordination

The U.S.-led Operation Prosperity Guardian naval coalition has provided some deterrence against attacks on commercial shipping, but with limited scope and uneven participation. Key allies including France and Italy have declined direct participation, preferring separate European Union naval initiatives.

This fragmentation reflects broader strategic divergences about appropriate responses to Iranian pressure. European allies generally favor diplomatic engagement and measured military responses, while Gulf partners seek more robust deterrence measures. The result is a coalition response that appears substantial on paper but lacks unified command authority or rules of engagement.

Operational Constraints and Trade-offs

Defensive Limitations

Naval convoy operations provide limited protection against the diverse threat spectrum Iran and its proxies employ. Surface combatants can intercept missiles and drones but cannot effectively counter mine threats, underwater vehicles, or cable sabotage operations. The asymmetric cost equation favors attackers—a $1,000 drone requires a $3 million interceptor missile to defeat.

Cable repair operations face even starker constraints. Specialized cable repair ships are few in number and vulnerable during extended seabed operations. The repair timeline for major cable systems ranges from weeks to months, during which service degradation persists.

Perhaps most critically, defensive operations impose unsustainable operational tempo on naval forces. U.S. Navy destroyers and cruisers in the Red Sea and Gulf have expended missile inventories at unprecedented peacetime rates while accumulating maintenance backlogs from extended high-tempo operations.

Escalation Management Dilemmas

Iran has masterfully exploited the escalation dynamics of chokepoint warfare. By using proxies for the most provocative attacks while maintaining direct Iranian operations just below clear red lines, Tehran has forced Western powers into purely reactive postures.

Military retaliation against Houthi positions in Yemen has proven largely ineffective given the mountainous terrain and dispersed infrastructure. Strikes against Iranian naval facilities would risk broader escalation that could genuinely close the Strait of Hormuz—an outcome far worse than current harassment levels.

The result is a strategic paralysis where defending powers absorb mounting costs while attackers retain initiative and escalation control.

Our Take: Iran has successfully weaponized the world's maritime geography without triggering the massive retaliation that outright chokepoint closure would provoke. This strategy of managed instability imposes persistent costs on global commerce while preserving Tehran's escalation options and regional influence. The West's reactive posture—protecting shipping at unsustainable cost while avoiding direct confrontation with Iran—suggests this campaign will continue indefinitely unless fundamental strategic calculations change. The world has entered an era where global trade arteries exist in permanent fragility, with risk premiums and alternative routing becoming permanent features rather than crisis responses.